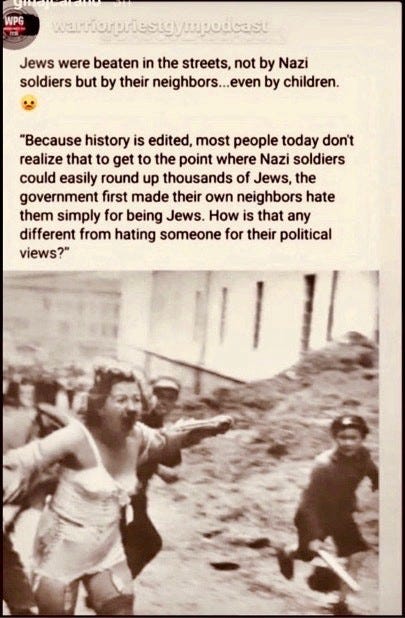

We’re coming up on a year since Gina Carano, the former co-star of the ultra-popular Star Wars spin-off series, The Mandalorian, was fired by Disney after sharing this Instagram post:

It landed like a firework amidst of the furor unfolding over rightwing extremism and the government response to the January 6th storming of the U.S. Capitol. As a vocal conservative, Carano was denounced, widely and instantly, for daring to imply that Trump supporters (of which she is one) and people on the political Right were being persecuted like Jews in pre-war Germany. Indeed, she was un-cast, abruptly, from her starring role for it.

Had I believed that’s what she actually meant I’d have sympathized with the pushback (though not her firing). But I thought it clear she wasn’t claiming a straight — and offensive — equivalence between the trials of Jewish people under the Third Reich and the troubles facing post-inauguration Republicans. I heard her making a more relevant and honest point: that when people buy into official messaging encouraging them to turn on their fellow citizens with punitive fervor, green-lighting them to demonize and dehumanize, they step onto a known and dangerous path. So I found it surprising — and rather dispiriting — that so very many people rushed past that obvious truth to decry a seemingly contrived claim.

Of course, it’s undeniable Carano set herself up for the controversy, first because of her support for a political leader known for his demagoguery and branded a racist by his legion of detractors, and second, because in the arena of politics and the culture war — and particularly the free-for-all of social media — leaning on the Holocaust to make any point invites censure. And for good reason. Arguments drawing on Nazi parallels tend to be shallow and imprecise, far more apt to trivialize history than illuminate its lessons.

Yet I didn’t perceive Carano’s post as shallow, despite its historical imprecision: the photo doesn’t depict a Jewish woman being assaulted in 1930s Germany. According to the website rarehistoricalphotos.com, it shows a Jewish woman in 1941 Lwów, Poland (now Lviv, Ukraine) being “chased by youth armed with clubs . . . fleeing from a ‘death dealer’ whose left leg can be seen at the left-hand edge of the photograph.” It seems it may be part of a series created by the Wehrmacht propaganda company, documenting the July pogroms in which thousands of Polish Jews were massacred in a matter of days by Ukrainian militia and Lwów citizens, at the behest of the occupying Germans.

Regardless of the details, few of us viewing that poor woman’s terror can fathom living in a society that could devolve into such soul-shaking brutality. As civilized individuals we recoil from the thought that we could ever stand witness to such depravity, never mind participate in it. The suggestion feels preposterous, even as a mental exercise.

Indeed, when we look back through human history at its more heinous moments and compare them with our current events, it’s easy to feel safe from the possibility we’ll ever repeat those mistakes. We may recognize a similar trend here or there, but we quickly identify the many ways in which our present situation differs from those past. We note with relief that the lines of cause and effect we’ve drawn, connecting portentous events of previous eras to their monstrous outcomes, can’t be easily redrawn in the present because times have changed . . . the issues just aren’t the same . . . our society is a different place . . . we’ve learned those lessons . . . we’re better than that. No worries.

Or so we imagine, and presume.

Mark Twain is famously credited with saying: “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes.” His words call us to recognize that of course the moment we’re in won’t mirror the past. We shouldn’t be expecting one-to-one parallels, looking for every facet to be exactly duplicated, assuming we’ll recognize the scenery as if we’re traveling a familiar road. History is said to rhyme because the external circumstances that define a moment, shape its significance, do not propel it. Human nature does.

History rhymes because underneath the changing contours of human events, human hearts and minds are a constant. Human cultures can develop, grow in their moral outlook and ethical practices, but human beings do not stop being susceptible to self-interest and contempt, to the impulse towards critical-mindedness and rationalizations, to the hard-wired need for tribe. In the grand sweep of history . . . ourstory . . . our universal human traits keep us vulnerable — individually and collectively — to the perverse and captivating madness of crowds.

In 2018, Brandon Stanton profiled survivors of the 1994 Rwandan genocide in his photoblog, Humans of New York*. One especially harrowing story he featured is told by the daughter of the man wearing the red tie in this photo:

Her story is one of shattering violence, of unfathomable trauma and loss. But even without reading it (which I recommend you do), her words shared alongside this final photo of the series should give all of us pause:

“This is a picture of my father before the genocide. He’s surrounded by his Hutu friends. They’re sharing beer. They’re talking. They always viewed him as a good person. They’d even come to our home and flatter us. They’d tell my sisters and me how good of children we were. And that one day we’d marry their sons. Many of these men would later help kill my family. So how am I supposed to trust anyone? Before the genocide, there were doctors taking care of their patients. Priests were taking care of their followers. Neighbors were taking care of each other. But none of that stopped them from killing each other.”

That, right there — that horrifying inhuman potential — is what Carano was pointing at.

Because it is a lesson of history that the callousness to suffering which allows atrocities to overtake civilized societies doesn’t appear out of the blue. The ground is laid through time, the seeds of alienation sown and cultivated by rhetoric that poisons the well of kindness, obscures, then erases, the humanity of the Other, spins convincing stories of Good (Us) versus Evil (Them) through which rage, or indifference, is justified. Stories in which permission to resent and exclude — to target — ends up granted through the ennobling of antipathy into virtue, the embrace of moral certitude into open hostility.

Of course, most of us rest in the conviction that we would not be among those willing to promote or excuse hatred. We would refuse to participate in merciless evil. And history shows that’s likely true. But the question remains: What would we do . . . ?

In his speech on January 27, 2020 commemorating the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau, Marian Turski, a (then) 94-year-old death camp survivor focused his powerful remarks on how the Holocaust came to be. He outlined the gradual process through which German Jews became ostracized as their fellow citizens became desensitized. Most striking is his description of the reflexive rationalizations, each step of the way, for tolerating—rather than resisting—the expanding restrictions on Jewish lives. Above all, he illuminates how a profound insensitivity towards the Jewish plight was cultivated through a policy of othering and incremental discrimination, and his words of warning here, addressed to that mindset of complacency, are in our current moment both chilling and timely:

“But be careful, be careful, we are already beginning to become accustomed to thinking, that you can exclude someone, stigmatize someone, alienate someone. And slowly, step by step, day by day, that’s how people gradually become familiar with these things. Both the victims and the perpetrators and the witnesses, those we call bystanders, begin to become accustomed to the thoughts and ideas, that this minority . . . is different, that they can be expelled from society, that they are foreign people, that they are people who spread germs, diseases and epidemics. That is terrible, and dangerous. That is the beginning of what can rapidly develop.”

Indeed.

Carano’s post may have contained a basic historical error, but her message wasn’t wrong. Or trivial. And we would be well-served to reflect on it.

Because we all know the Final Solution did not begin with cattle cars and gas chambers, it ended with them. And pointing out that fact of history — that an intelligent, educated, civilized population was actually moved to indulge, to excuse, or even just to look away from that depraved finale — cannot be off-limits in our political moment if that history is to have any use to us. Because we know tribalism is an easy sell. Contempt, especially when given official imprimatur, presents a deceptively comforting path. And moral courage, to stand up against a malign message when it means risking the security of belonging, risking oneself and loved ones becoming targets or outcasts, is undeniably the road less traveled.

So let us not relax into the naiveté — or hubris — of believing the mistakes of the past are beyond our potential to reiterate. Let us instead attune ourselves to history’s rhyme, to its intimations in our present and stand bravely for love, that we might not lose sight of one another’s humanity, that we might never — individually or collectively . . . actively or passively— be convinced to forsake our own.

* NOTE: To view HONY’s Rwandan series, click on the hyperlink and use the Left arrow on each photo to scroll. The story I referenced was shared on October 24, 2018.

This is mostly a wonderful essay.

I strongly disagree that one should not make comparisons to the Holocaust, or only do so rarely. Nor should one take offense merely because someone makes an inapt comparison to it--or, rather, one you happen to find inapt.

In fact, we should reference the Holocaust, as well as the few other historical events where we can agree people and governments committed atrocities. We are supposed to learn from the past. We cannot do so by shutting our minds to the idea that anything like what happened at particular place and time to certain groups cannot happen now. Indeed, that is part of your point.

Note that it is the fact that Carano posted the comparison that started an important conversation. If people are afraid to discuss the Holocaust, then people might not have the discussion. It is easy to avoid this chilling effect--let people speak. If they are wrong, others can disagree. Dialogue.

People have been trained view Holocaust comparisons as flawed, suspect, or possibly "offensive." Just people have been trained to view criticism of the state of Israel is suspect, often reflexively labeling it anti-Semitic. This is wrong. We cannot avoid repeating the past if we cannot think about it in connection with our present and future. We cannot have a free society without the freedom to think and discuss.

Beautifully written. Let us pray that better angels will prevail over the demons who are fomenting hate everywhere.