What are you willing to risk in order to free yourself from the mob in your mind (self-censorship)? I ask this question because I’ve come to realise that most of us are not willing to risk anything. Especially our comfort. But without taking some kind of risk (one that won’t leave you in utter chaos), you will continue to consult that mob before you consult yourself.

~ Africa Brooke

When I was in ninth grade I had a religion teacher who began each class by rising from his chair and intoning: “Stand UP for the TRUTH!” Dutifully, my classmates and I would rise to our feet, using our material bodies in symbolic service to a spiritual cause.

Forty years later I still ponder that admonition. In fact, I wrestle with it.

The thing I often come back to is the social angle: When do I stand up? And how? Because like a lot of people, I want to stand courageously for what I believe, not silence myself for the sake of feeling comfortable, fitting in. Yet, I feel the weight of concern for how my words fall, for their repercussions both in my own life and relationships and in those of others. So I wonder: How does one speak honestly when the measure of kindness is the avoidance of hurt, the measure of compassion the protection of feelings? How does one stand for truth in a culture that spurns discomfort and pain as a path to growth? And I ponder the risks of self-censorship for the health of individuals and society.

To be clear, by self-censorship I don’t mean observing social niceties like “white lies” to spare pointless hurt, or holding back gratuitous criticism. I mean refusing to say out loud—or perhaps just openly signal agreement with—something you believe is true because you fear backlash: judgment, stigma, social rejection, condemnation. How powerful is our impulse to go along to get along?

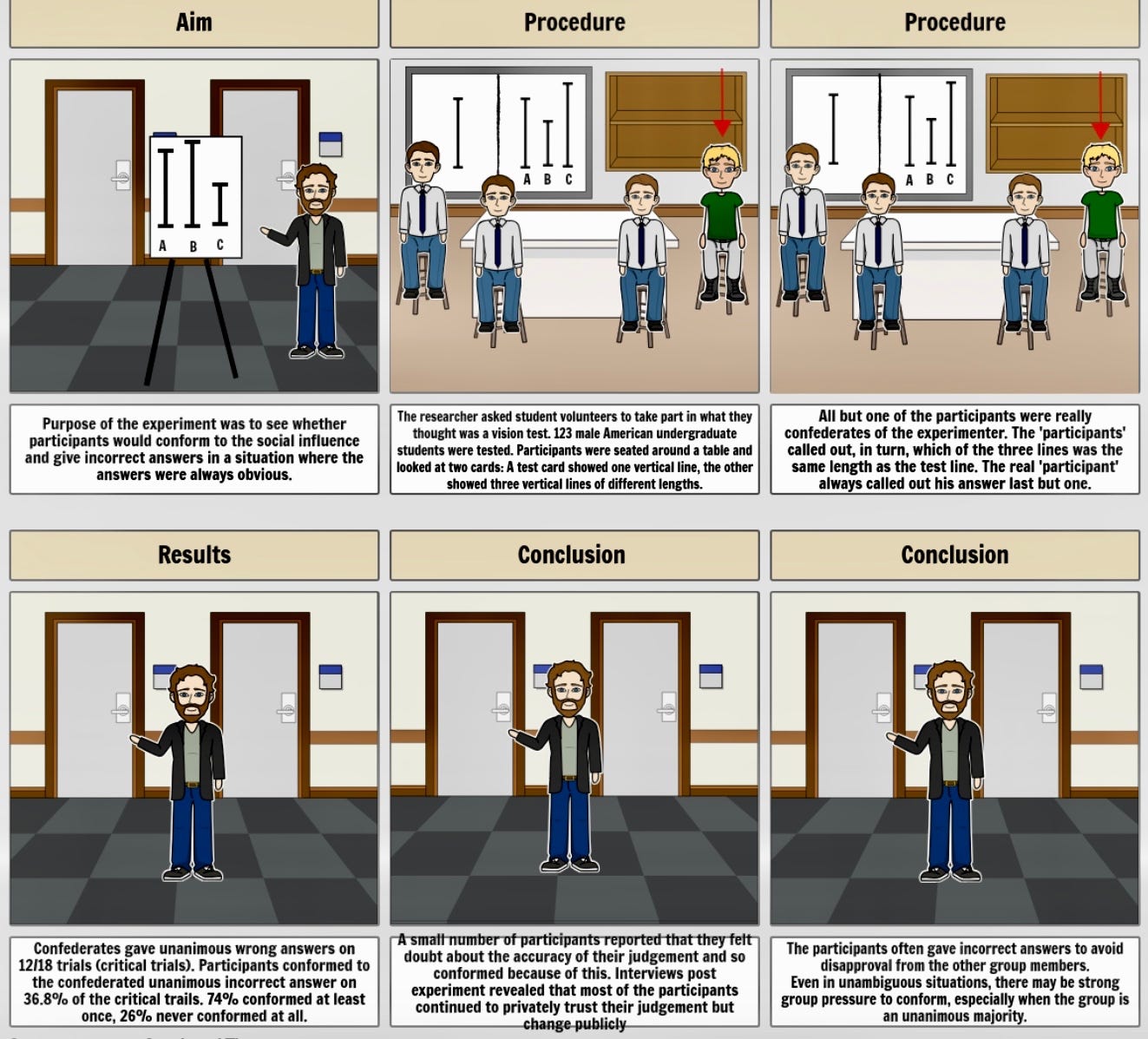

We know from social psychology it doesn’t take much to prompt people to self-censor. The famous conformity experiments conducted by Solomon Asch in the 1950s showed that only 1 out of 4 test subjects could resist agreeing with a clearly incorrect group consensus. Indeed, what’s surprising about the study is that three quarters of test subjects were willing to vocally match their own answer to a wrong consensus at least some of the time despite how objective and inconsequential the test question was: they were being asked—supposedly as part of a vision test—to identify which of three lines matched a reference line. And three out of four test subjects voiced agreement, at least once, with an unmistakably incorrect answer after it became the group consensus.

In the critical trials of the Asch study, each test subject was experiencing social pressure to cede his grasp of reality, to conform to the group consensus even though it was obviously, indisputably wrong. In post-experiment interviews, many said they knew the true answer but went along with the group for fear of ridicule or standing out as different; a few said they agreed with the consensus because it caused them to doubt their own perception. Clearly, social pressure to go along to get along, even when it requires denying an insignificant obvious fact, is a real and powerful force.

So then, what does it mean for society when the truth at stake is not insignificant, but fundamental and far-reaching? It’s worth discussing, because while we might assume anything of significance would elicit allegiance to accuracy over self-censorship, across the Western world people are under pressure to deny one of the most basic and obvious truths of human biology: that sex is binary and immutable. And the campaign for conformity is growing, spreading, even becoming institutionalized. Meanwhile, for both individuals and groups, the consequences of such denialism are already proving destructive.

A recent example which brought this issue starkly to the fore is the 2022 NCAA Championship title that Lia (née William) Thomas was awarded in the Women’s 500-yard freestyle. Thomas, a Division I swimmer who ranked 65th in the men’s event before undergoing gender transition, was presented the women’s gold trophy having reached the finish ahead of the female field. Of course, he did not in truth win that women’s title for the simple reason that he is not female—material reality was not altered by his newly declared self-perception nor by the inclination of others to honor it. So, regardless of his final stand atop the podium and the gold being handed to him, the win was not true: he was not actually the woman who finished first. Like the child pointing out that the emperor is naked, our own eyes can see the reality of the matter:

The argument for Lia’s claim is that being a woman is not defined by any material fact of biology but by a subjective experience of the self: a personal sense of gender. Another way of saying this is: whoever “feels like” a woman is a woman, and whoever “feels like” a man is a man. Setting aside the immediate existential question of how anyone can know what it “feels like” to be anyone other than themselves (much less the opposite sex), this is a claim that wholly discounts the well-established, concrete implications of male and female sex differences with regard to functioning, abilities, and health. It is a claim moored in postmodernism, from which comes both its denial of objective knowledge and its reliance on linguistic deconstruction. Specifically, it proceeds from the branch known as Queer Theory, which advances the “queering” of society—the disruption and subversion of all “heteronormative” beliefs, values, customs, and practices through a deliberate transgressing of all boundaries, starting with sex and gender. The supporting logic for this argument is thus, not surprisingly, a tangle of sophistic claims the gist of which is that human genetic sex determination is actually an unpredictable, variable-driven process that leads—more easily than any of us ever realized—to mismatches and interpretive results. According to this new understanding, gender perception should thus be championed as more reliable to establish the classifications of “woman” and “man.” In fact, we are now being prompted to adopt the new vocabulary that our sex is “assigned” at birth rather than observed and recorded—that it should be considered a temporary designation subject to clarification by each individual’s eventual self-declaration.

In short, the argument propelling gender ideology relies on a philosophical framework that negates not only our eons of history, but our scientific grasp of our species’ sexual dimorphism, redefines the words we use to navigate human biology, and so seeks to decouple it from material reality. (If you want to delve into considerations of why this is happening, read extensively here, starting here.)

I’m not raising this issue to invalidate the suffering of people who struggle with acute gender dysphoria, which is real and can create persistent, even excruciating, psychological distress. Nor would I claim no adult is ever served by transitioning socially, or in some cases medically, to live as the opposite sex. I am saying this to make the once-undisputed point that the physical world with its concrete limitations matter. The language we use to describe and communicate it matters. And the repercussions of pretending otherwise will increasingly matter as they injure the innocent, cause lasting iatrogenic harm, and destabilize society. This is why, in discussing Lia Thomas, I am using male pronouns rather than following the new norm of defaulting to preferred pronouns. Because by being permitted to compete in the female division with the profound material advantage of being a post-pubertal male, his capture of a women’s title offers a conspicuous example of an injury that is compounded by capitulating to the polite fiction that he is actually a “she.”

Consider: without Lia Thomas in the women’s competition, Reka Gyorky would have been ranked All-American and swum in the consolation final, Tylor Mathieu would have advanced to the finals, Brooke Forde would have won the bronze trophy, Erica Sullivan would have won the silver, and Emma Weyant would have been awarded the gold trophy and the well-deserved title of 2022 Women’s NCAA 500-yd Champion. Instead, none of these five women were recognized for their true achievements. They all were displaced, bumped from their earned ranks and opportunities by a male whose body—12-plus months of testosterone-suppressing drugs notwithstanding—enjoyed a material advantage comparable to a female doped with the performance enhancing drugs universally banned from sports. And this was permitted in the name of fairness and compassion, to honor and make space for the trans identity of a young man who wished, post-transition, to continue participating as a college athlete.

I have to ask: Where was the concern about fairness and compassion for all the young women suddenly stripped of an even playing field? Why did Lia’s dreams and goals for success as a competitive swimmer deserve—and receive—priority over theirs?

One obvious rebuttal to my concern is that two of the swimmers who lost to Lia—Brooke Forde and Erica Sullivan, both Olympic silver medalists—openly supported Lia’s participation in the Women’s Division. In fact, prior to the NCAA championships, Brooke Forde released a statement saying: “I believe that treating people with respect and dignity is more important than any trophy or record will ever be, which is why I will not have a problem racing against Lia at NCAAs this year.” And the month before the NCAA championships, a letter of support was signed by over 300 current and former U.S. collegiate, Olympic, and international swimmers, declaring that transgender athletes “deserve to be able to participate in safe and welcoming athletic environments.”

It’s hard to push back against this noble aspiration to put people ahead of personal ambition, to foster an ethic of welcome and inclusivity, because good sportsmanship and communal bonds are key to any healthy competition and to society.

But so is fairness. And like it or not, fair competitions are delimited by material reality. That’s not a choice, it’s a fact. It is precisely why women have had their own sports leagues. It is why weight classes exist in all size-dependent physical contests like boxing, wrestling, and weight-lifting. Material reality matters. And throughout all of history humanity knew and acknowledged that truth, until about five seconds ago.

So again, I have to ask: In the admirable concern for respecting individuals and protecting their dignity as competitors, why was Lia prioritized over every one of the female athletes? I also wonder: while there appear to be many top swimmers supporting Thomas’ inclusion in the women’s division, how many signed that open letter from sincere conviction and how many from social pressure: fear their silence might be construed as “transphobia”? Did any simply go along to get along?

Which brings us back to self-censorship.

Most people don’t want to be seen as callous to the suffering of others. No one wants to be labeled bigot, which has become routine if one openly questions the admission of males into female categories and spaces. Few people, however privately dismayed by a man being awarded a women’s title, feel disposed to publicly criticize seemingly goodwill efforts to include conflicted people in the communities to which they incline. And so people’s best neighborly impulses—their desire to show support rather than add to another’s burden—are being harnessed by a destructive ideology to clear a path for the queering of natural boundaries. This cynical movement has co-opted the language of both civil rights and self-actualization in its campaign to confound the human sex binary and thus erase, in law and language, the materially real—and crucial—categories of “woman” and “man.” And as this queering of biology flies beneath the banner of “inclusivity” and “love,” anyone who expresses doubts or criticism becomes, de facto, a champion of exclusion and hate. I’ll be honest: writing on this topic I am nervously aware of defying a new and powerful norm regarding acceptable discourse. Since I began this essay in February I’ve abandoned it for weeks at a time, caving to my own self-censoring impulse as I anticipate that many will see me as hard-hearted for speaking out, will claim my perspective and language devoid of understanding or deeply transphobic. And knowing most who agree with me will decline to do so openly.

Which is why I have to bring it up.

Because what does it say about our society that caring, sincere individuals who are concerned about the well-being and suffering of others, about harm to innocents, who are concerned about the health and cohesion of their families and communities, can no longer candidly discuss biological reality, must tiptoe around the facts of its limits or ignore their significance, for fear of exposing themselves to charges of bigotry, ignorance, or cruelty? It’s an impossible bind—the desire to stand as a loving and compassionate human AND as one who recognizes empirical truth and its implications. One who does not believe material facts should be . . . can safely be . . . redefined or papered-over to validate the earnest delusions of struggling individuals. It’s as though we are being forced to choose: either speak what is observably true from the evidence of your eyes, or speak what feels kind from the generosity of your heart. But honesty and compassion cannot be aligned so you can’t do both.

It’s time to acknowledge that quandary for what it is: a false dichotomy.

We all see it clearly in the analogous situation of an anorexic consumed with hatred for her body, desperate to rid herself of non-existent fat. We know compassion for her pain does not call us to affirm her distorted self-perception nor does it demand we support her risking her physical health to alleviate her psychological distress. We see that genuine kindness involves holding fast to material reality and refusing to join her delusion, pretend her feelings signify the truth of the situation, regardless how anxiously she desires that “support.” Indeed, contrary to the framing rigidly imposed by True Believers of gender orthodoxy, kindness and affirmation are not equivalents. They are not always or inevitably the same act. In fact, sometimes they are entirely opposites.

And so we also must acknowledge this human moment for what it is: a spiritual trial.

We all are being called to stand up for truth. We’re being called to risk defending what is real for the sake of protecting everyone who will be harmed, everything that will be lost, by craven collective silence. As individuals and communities, as a culture, our moral character is being tested, awkwardly and unexpectedly. It is time to discover our courage to speak, to recover our sight and spine and refuse to cede reality to sophists, surrender what we knew until five seconds ago to be uncontroversially and uncontrovertibly true. And to do this from love—from an honest concern for human flourishing, for what is lastingly good, helpful, and—yes—kind.

Solomon Asch’s experiment revealed not only how easily people self-censor into conformity, but how easily they can be encouraged to speak truth. In the small sample of his study, all it took was a single confederate naming the correct line for the test subject to feel secure to declare it also. In our current moment nearly all of us understand the value of empirical reality. We see the emperor is naked. We know human sex is binary, immutable, that material reality matters. So let us stop participating in the fiction that the emperor’s clothes are real. Let us stand together, with quiet confidence and open hearts, and declare what is true out loud. Because kindness and honesty—love and truth—are by no means incompatible. In fact, they are spiritual confederates. And in our continuing human quest for health and happiness, they make the strongest, most reliable allies.

We are approaching the brink; already a universal spiritual demise is upon us; a physical one is about to flare up and engulf us and our children, while we continue to smile sheepishly and babble:

“But what can we do to stop it? We haven’t the strength.”

. . . Our way must be: Never knowingly support lies!

~ Alexander Solzhenitsyn

Years ago I happened to sit next to an archbishop in the Armenian Church on a plane from Seattle to Burbank. What started with me inquiring about the alphabet of the book he was reading turned into one of the more memorable conversations in my life.

It was one of those extended exchanges where you find yourself putting something together intellectually that resolves an almost spiritual discomfort. It was this: I told him I was not a Christian. I said I would rather face God as a non-believer and say I lived with integrity to a lack of faith than the other way around.

How could God desire anything other than integrity? If I do meet a Maker someday I hope that I have the courage to stand my ground in the face of a forbidding and incontrovertible rule book. The Archbishop was an extremely warm and generous man, but he did not or could not agree. On the way out of the plane, he turned to me and gave me a small cross he kept in his clothing. I'm guessing he kept a handful of them for exactly this kind of interaction.

I took it from him and thanked him genuinely - this after a pretty large fissure opened up between us on faith and integrity. And this is important. I disagreed with him in the chair and, in a fashion, agreed with him while filing out. Very different things mattered in each context.

You've written this essay so thoughtfully and with such care that I want your opinion on something if you have the time or are inclined to give it.

I don't know if I've made this up myself or borrowed it from somewhere, but there's an idea that character is what we choose when faced with conflicting values. If you are a writer of a story and you want to demonstrate something about a character's character - then force a decision between two values that are both resonant/valid but also in conflict with each other.

This is very much at odds with Solzhenitsyn's blanket - "never support lies!" This strikes me as a philosophical and dogmatic rigidity that looks at all choices as binary and in isolation from each other. There's something in the conservative temperament that's often hard here.

I can almost guarantee that there are times when "never support lies" for Solzhenitsyn himself would have come into conflict with an opposing value where "never support lies" lost out - on someone's death bed I'll use whatever pronoun somebody wants period full stop because not coming into conflict with someone's view of themselves and the world when they are leaving the world would be a higher value for me. In a courtroom a different value would win. I think you can establish my character, Solzhenitsyn's, your own based on this tension between values. One might not believe in God for example and still close your eyes for a prayer at the Thanksgiving table.

With the Archbishop when I was in my chair, I was ready to challenge his faith and his God, but when we were filing out I felt that the awkwardness of how he presented the small cross was a true act of kindness that I wanted to honor. So, I did. I'm consistent to my value system, even if my behaviors are not consistent to my emperor's clothing system. It forces me into a grey zone where I'm not consistent, but it also has - feels like - a more organic, nuanced relationship with my values: sometimes one value loses to another.

I think this nuance shows up with the other swimmers wanting the male swimmer to participate in the female competition. Some of this could be social fear, but some of it can be that it is genuinely more important to not shame someone in any way than to win an athletic competition. The parent of the swimmer and the coach might have exactly the same two values in play but come out emphatically on the opposite side.

Do you think that one can believe something to be absolutely true (with an Emperor is Wearing No Clothes confidence) and still find "telling the truth" to be secondary to another value? Or is this fairly black and white? What am I missing? What can you add? Subtract?

You've done your mental homework here and there is goodwill in your work (I've only read one other article, but you have my attention), and I'd love your thoughts. You are reasoned and insightful. I'm just finding the Solzhenytsin insistence on truth "off" somehow, rigid, missing something. That even the black and white Emperor's issues aren't so cleanly dispatched.

This is an extremely moving, and thought-provoking essay. You've covered a lot of very complex issues in this piece and raised some very important points. I certainly am not sure what the solution is, if there is one. I think it's going to take a lot of effort on a variety of fronts to change the tide. One such effort would be a series of very vigorous, high profile, high dollar lawsuits against the medical practitioners of these gratuitous surgeries.

Your opening point — that we have to stand up for what we think is right — is certainly true. However, for a variety of reasons, for some that's not possible. Those who can, should. And those others should support those who stand up. Thank you for this very interesting piece, Frederick